John Locke

John Locke was another Englishman and a near contemporary of Thomas Hobbes. He built on Hobbes' work to create the practical framework of Western political theories and systems. The framers of early modern democracies—like the United States—would derive significant portions of their political language from Locke's work.

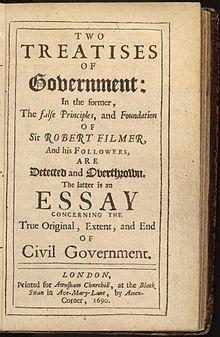

Locke takes Hobbes’ idea of the consent of the governed as a given. The power of the sovereign and parliament comes from the population giving them power, rather than some sort of divine ordination.1 This leads to his support for democratic systems because they represent the rights of the people. Rather than ceding all a personal freedoms and having to accept sovereign decisions without question, the populace are represented by the government and consent can be revoked.

"Men being, as has been said, by nature all free, equal, and independent, no one can be put out of this estate and subjected to the political power of another without his own consent..." 2

This idea of consent not being permanently binding goes against Hobbes' ideas of absolutism and, thus, previously prevailing political theory. Locke argues that no man intends to subject themselves to absolute and arbitrary power because they would be worse off than how they are in the state of nature.3 When subjected to a singular, arbitrary power, he argues, a person has little recourse to go against the sovereign’s rule. If this was the case, people would have little ability to protect themselves against their rights being infringed upon.

"The state of nature has a law of nature to govern it, which obliges everyone: and reason, which is that law, teaches all mankind, who will but consult it, that being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions." 4

As seen in the above quote, Locke articulates the idea of inalienable rights—rights that no person, sovereign, or government can take away. This idea permeates throughout Western political thought and, thus, becomes the foundation of what is later known as human rights.

With his idea of inalienable rights, Locke also articulates the idea that people have the right to resist unjust rulers. If the people’s inalienable rights are threatened and the injustices the sovereign imposes on the people are no longer tolerable, they have the right to dissolve the government and establish a new civil society.5 Since these rights are inalienable, when they are harmed or otherwise infringed upon, the people have the right to protect themselves and their rights from further abuse. In this, Locke articulates the ideas which would justify the American Revolution.

1. Locke, John. Second Treatise of Government. Edited by C. B. Macpherson. Cambridge, MA: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 1980, 52: §95.

2. ibid, 52: §95.

3. ibid, 9: §6.

4. ibid, 72-73: §137.

5. ibid, 111-113: §222-223.